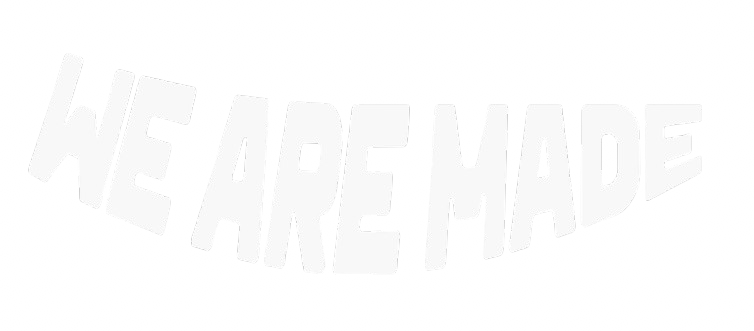

Tracey Africa early beauty campaign (1971) (All rights reserved to owner)

Camille Lawrence is the founder of the Black Beauty Archive, a digital platform dedicated to preserving and celebrating the history and artistry of Black beauty culture. With a background in beauty, curation, and storytelling, she created the archive to honor the contributions of Black creatives and ensure their legacies are documented for future generations. Lawrence's work bridges the gap between beauty and cultural preservation, empowering communities through intentional representation.

You studied Art History in college and worked as a makeup artist to support yourself through school. Can you share what the early moments of resistance looked like when you first introduced the idea of merging these two separate worlds?

CL: I started at John Hopkins, and then Trump was elected in 2016. When he was first elected, there was a government shutdown that shook the museum industry and closed down many permanently. It was then where I said, I'm not going to allow a crazy tyrant to dictate my career. So I was like, “Where can I still be adjacent but have a little bit more flexibility?” While I was working at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, I stumbled into the archive by accident, and I fell in love. I fell in love with the idea that there were jobs that existed where you are the decision maker about what history is kept or discarded. I won't lie though, in my first week in the role as an archives assistant, I did struggle on the way home from work because I never realized that it was as simple as “Does this interest us or nope? Move on.” That really rocked me, and in a room of old white people, it shook me. So as I'm working and learning this, my resistance was always there. I was kind of like a militant kid, but my resistance in my workflows where I started tracking what things they chose to discard.Three months in, I proposed an initiative to them. I said, “I'm coming here, and I'm only focusing on Black stories, Black collections, Black histories.” We hear enough of these white names in repetition because they amass money when they're alive. They leave money in their will to keep the jobs paid for archivists and historians to keep their names alive. And sometimes we're not thinking about that planning, and/or we don't have the capital.

So I kept pushing through Brooklyn Academy of Music, Pratt Institute, and then I got linked up with Urban Bush Women. That's where I became the primary archivist, where I was able to build an archive from scratch for a 40-year-old institution.

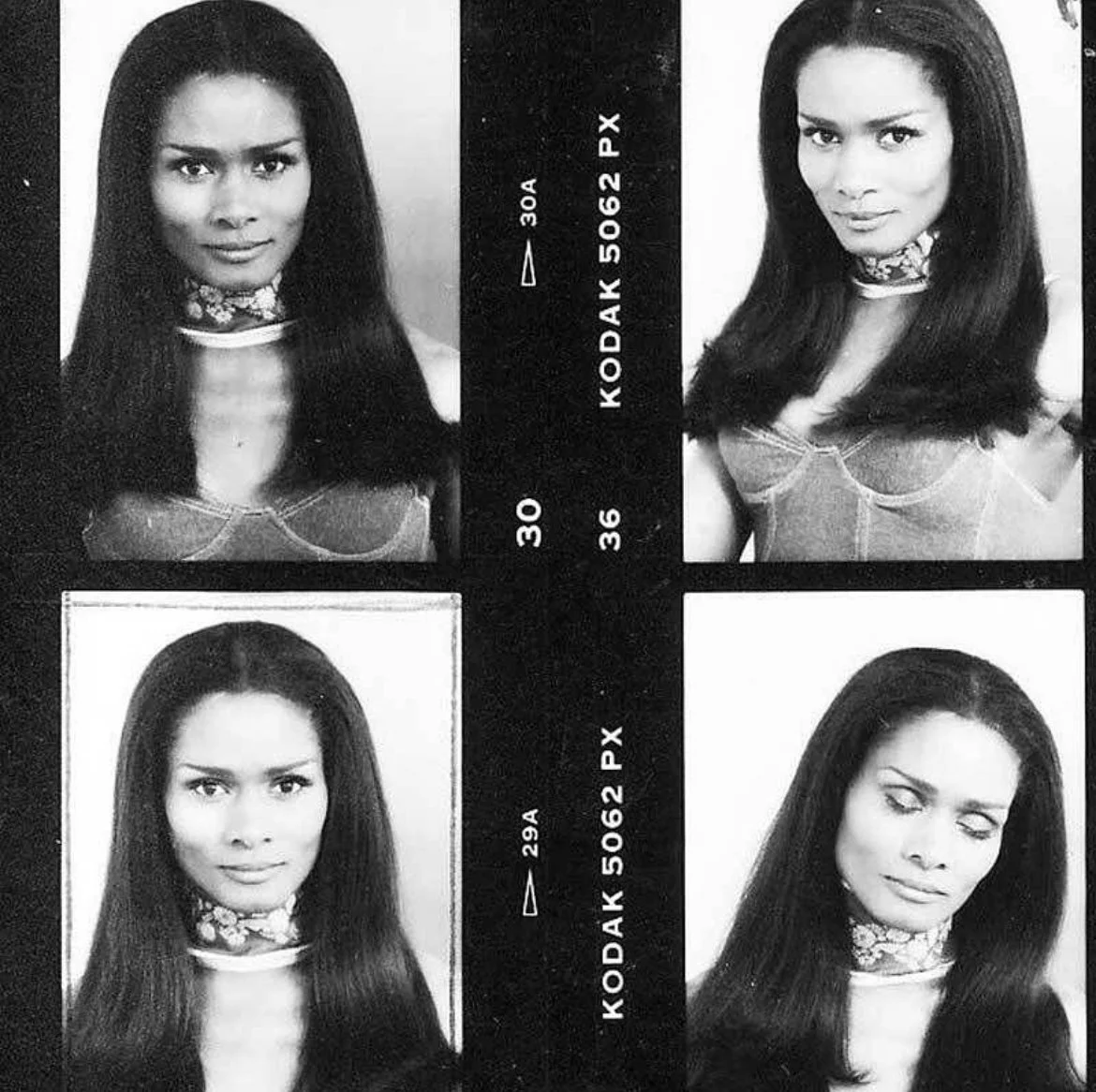

Lady Barbers Universal College (1971) (All rights reserved to owner)

Oprah Daily shared the story behind the creation of Black Beauty Archive, take us back to the moment it all started. What was going through your mind the night you woke your husband up with the idea to fill a major gap in how Black beauty is remembered and preserved?

CL: I started drawing these lines between beauty's performance; it started making me think, “Where's a Black beauty library?” So in 2020, I'm searching—I don't find it. The pandemic hits, and I'm like, I want some inspiration. So I made a little library. At first, I was thinking, “Oh, let me make a Lemonade syllabus.” I don't know if you saw that when Beyoncé’s Lemonade album came out. I thought, let me think of something like that, and I was like, “Oh shit, it doesn't exist.” There was one Black beauty museum that existed, but this Black woman scholar in the South, she was focusing solely on pageant history. I was like, that's not my expertise, so she got that. I'm going to go do this. So I started it with the intention of making a resource for all my friends in the beauty industry who are working on set, who are working on period pieces and films, to reference this accurately. Because when we're pitching to directors and brands, they put us through the wringer—Black artists more than anyone else. And because of the way that Pinterest, Google, Instagram are set up, the algorithms are not prioritizing our beauty nor affirming that our beauty standards are built on ancestral practices. There's innovations here. There's levels of legacy that are in our braids and our locks, et cetera. So I thought, how do I build a collection? I guess I'll start with Black-owned publications. I already had some Ebonys and Jets, but my husband has a sustainability company, and it was when he came upstairs one day and was like, “Yo Camille, I had this box; I think I'm going to give it to you.” Inside was like 50 more magazines. So at the same time in the pandemic, we were getting these little stimulus checks. What did I do with my stimulus checks? I saved them, and I built the archive. And so that's how I got money first to do acquisitions.

“Representation is important because Black children also need to know that there are black people in the future.”

- Camille Lawrence

What are some challenges you've faced in getting this work recognized or funded? And what lessons can others take from your journey as they try to build something just as meaningful?

CL: I pushed myself to learn new skills to work in tech, and I take my supplemental income I get from tech to fund the business. As you know, research shows most Black women don’t get capital for our businesses. It’s not until it blows up where people pay attention. Now, it’s been a little bit more difficult for me because I’m not selling a product; archiving is not sexy. And I’m also not a clout chaser, so I don’t have a personal social media presence. I chose to remove my digital footprint because I don’t want to be in digital spaces like that, but I do want to hold space for community, and I do want to tell our stories online. So our biggest engagement now is through Instagram, and it’s interesting because we created a post about the very Black history of nail culture, and that made us get 10,000 followers in five days. That’s also a testament to going against the algorithm to do something that feels good to you, and if it resonates with community, that’s affirming.

The work of Lupita N-Yongo (All rights reserved to owner)

How do you hope the archive will evolve in the next five or ten years?

CL: Making the database accessible for all people. Some stuff will be behind a paywall—that's really rare—but I'm always committed to keeping at least 500 objects front-facing. We will always put together free materials on social media. We will start creating K through 12 educational guides for teachers to start accessing the materials to teach. Because what we have in the archive touches every subject area, especially because we have full-issue magazines from 1941 to present day. Not only Black publications, but a lot of magazines where Black people were the first to break the cover or the first to be featured, specifically in fashion and beauty, but also culture magazines. So the goal in prayer is to inspire, create, recruit future archivists and archivists to make sure that we can build relationships to preserve this history in perpetuity.

I think that's the biggest challenge that I'm facing right now: getting funding for long-term preservation and perpetuity, as in when the file formats of technology change in 50 years. We don't have VHS tapes no more; we don't have VHS players either. We have to pay people who are experts in digital preservation to update these file formats, to convert them. People are not thinking about that. But thankfully the collection is coming from a physical, so we have the master physical files. We can always bring them into whatever is the new digital format.

What role does representation play in helping the next generation believe that their dreams and aspirations are truly possible?

CL: Representation is one of the essential pieces. To affirm that, number one, we've been here; number two, that dreams are feasible and people can actualize them; and number three, representation is important because Black children also need to know that there are Black people in the future. A lot of times, we need to see someone else who's a risk taker, someone else who looks like us, sounds like us, moves like us, to make us feel affirmed. I feel like I've gone through a lot of institutions and a lot of forms of respectability politics, and as an adult who's finishing a master's, I still choose to use colloquial euphemisms or AAVE and have to learn how to adapt and adjust to meet people where they are—to speak to the communities who need to hear what we're saying.

So I think representation is important because Black children also need to know that you don't have to put on a whole new identity to step into something that feels challenging or something that feels foreign or new. You can show up as your most authentic self and still do good work and still be seen. And the authenticity of self is where the innovation happens, it’s where the trailblazing happens, it’s where the idea-making happens.

If I did not know Black archivists existed, I don't think I would be doing this. If I did not know that Black historians existed, I don't think I'd do it. And if I did not realize the pillars in the Black beauty community and industry were still moving and shaking—because I can see them on Instagram, because I can hear their voice on TikTok, and listen to their interviews on YouTube—then I wouldn't believe that I could do it too.

Want to hear more amazing stories like this? Check out our “More of Us” series! If you want to connect with Camille and support the work she is doing, follow her on social @theblackbeautyarchive.